|

Alpine Fir Adventure

|

| Remote in the depths of the Olympic Mountains, is earth's largest alpine fir. To visit this enormous tree requires an arduous four day hike. When the fir was initially measured in 1964, foresters marveled at its massive trunk having been carefully hollowed long ago by an explorer or hunter, to serve as an arboreal storehouse. Learning of a tree so huge and interesting, I burned to see it. After all, 28 years had passed since it was declared the largest known, so there remained the question of whether it was even still alive, and if so, how big was it now? |

| Olympic National Park consists of mountains and valleys, including famous rain forests. The Hoh is one of the mightiest rivers, and near the headwaters of that river is Cream Lake, nestled in a broad subalpine valley at 4,400' elevation. To reach Cream Lake and the giant fir, one must forsake the well-traveled official trail system, and head high into trackless backcountry. |

| The best time to hike is in late July or August, because of minimal rain, long days, and many delicious berries. It seemed foolish to go alone, and too many people would be slow, so I went with one companion, Bob Van Pelt, Washington State's big tree expert. We began tardily, however: on the last day of September. The flowers were spent and the berries all gone; coolness had replaced the summer warmth. |

| The trailhead is "Whiskey Bend" of the Elwha Valley, southwest of Port Angeles on the north Olympic Peninsula. From there to a footbridge over the river is a 3-mile woodland trail, gently rising up and down east of the roaring river. Before the Elwha was dammed, it supported Chinook salmon averaging 100 pounds -- weaker fish couldn't make it to spawning grounds above a difficult canyon named Goblin Gates. |

| At the Elwha bridge, elevation is 875 feet. Here the climb begins, which eventually tops at 6,157' on Mt. Ferry. The trail up is called The Long Ridge, a name right on target, if not poetic: 11 uphill miles to 5,500 feet, where we would spend the first night. Along the way the trail passes most kinds of trees native to western Washington. The forest changes gradually from lowland river species such as willow, cottonwood, grand fir, and maple, to mountain hemlock, yellow cedar, alpine fir, and an increasingly prominent shrub and groundcover layer, wildflower meadows, and altitude-stunted trees. By the end of the day we were relieved to pitch our tent, the symbol of rest and shelter. Black bears, mountain goats, shrill marmots and birds ranging from ravens to juncos were our only associates. |

| Shortly after dawn the next day, we set off toward the pass, hoping to get to the sought-after fir, measure it, and make our way back to our gear and tent before dark. We were in for a surprise. It chanced that although the route was straightforward until we reached Mt. Ferry (half way), thereafter was no trail at all, and a terrain far more rugged than the map had led us to expect. Standing atop Mt. Ferry, our high point, we admired an unbroken range of jagged snow-capped mountains, below which swept forested valleys, deep green where foggy clouds weren't hanging over them. |

| We had enough food and water for a day expedition, but as hours passed and the sun sank, it was clear we were in for a night without tent, sleeping bags or even a comfortable amount of food. Thirsting to see the tree, we didn't care. But, as the landscape before us filled with mist ascending from the Hoh Valley, obscuring the sun and blue sky, our spirits sank; we felt cheated of lovely sunshine, now in our time of need. |

| After descending first among boulders, then meadows, and finally clumps and patches of mountain hemlock with no alpine firs, we were relieved to find the Cream Lake basin to be a vast fir forest. The basin was flat and broad, a plain dissected by gurgling streams of glacial meltoff, supplying Cream Lake with clear water to belie its name. |

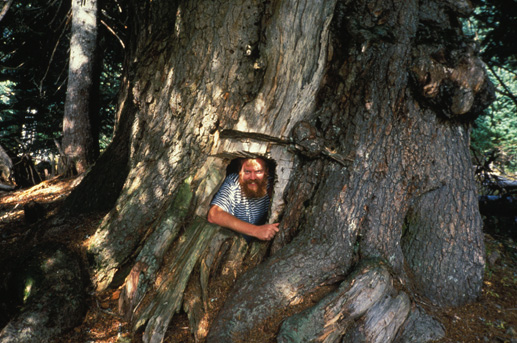

| After a twenty minute search, the tree was found, truly transcendent in size. As if miraculously, the sun broke through the gray mist and illuminated the valley, revealing high ridges and mountains ringing us. Green were the hillsides, blue the sky, and we joyously snapped pictures of the tree, taking turns climbing inside its cavernous trunk. There was now nothing remaining of the "neatly affixed door" it once had, nor of a sign that proclaimed its champion status. But it was still alive, healthy enough for a 500-year-old, and growing, albeit slowly. |

| Alpine growth is always slow, and the largest annual rings visible in the tree's hole were about an eighth of an inch. The tree's base was a mere hollow cone, a thin band of living bark and wood gripping the soil. Doubtless a mighty wind will sooner or later topple the titan. The trunk had not increased measurably since 1964, still being 21 feet around. Alpine trees often put their energy into foliage, cones and upper trunk wood, so this fact was unsurprising, although disappointing. |

| In 1964 the fir was 129' tall. We took three height readings; the average proved, to a dead tip, 124.3 feet. Alas, a decrease; presumably in 1964 the top had been fully alive. The tree's width or branch spread had been 15' in 1964, but was now 22' wide. So, our journey had proved the tree was still alive, growing at a barely perceptible rate. Should it die or blow down, we know none anywhere near as stout, although many are taller. The tallest in the valley was 156', and the next largest trunks perhaps 17' around. |

| Having measured and photographed the tree, we still had "a nest" to devise for our night's rest. The site chosen was a massive five-trunked mountain hemlock in a thickly-wooded slope that guaranteed minimal exposure to wind, rain, or cold air accumulation. We cleared the sleeping spot of branches and twigs, then cushioned it with springy hemlock cones. For cover we snipped alpine fir boughs. |

| Wearing all our clothes, we lay down back to back at dark. After two hours of sleepless shivering, though on a comfortable surface, we built a fire and spent the rest of the night huddled by it, alternately sleeping and feeding it. Warm, resting, and dry despite the fact that it was now raining, we could hardly complain, although we did not look forward to a spartan breakfast the next morning. |

| We sat by the crackling orange flames, feeding them semi-dry deadwood, listening to the calm hooting of a spotted owl, wryly desiring marshmallows to roast, but really relishing the feeling of being snug in the midst of a trackless wilderness in the remote mountains. We figured to be fairly lucky. The sense of inviolate nature was broken only once, as a distant airplane passed overhead, very high. |

| Dawn brought fog and 200-foot visibility, with moisture condensing on our hair and clothes. Uggh. For breakfast we shared one tin of sardines and a handful of dried apricots, with water. Enough to whet, but not begin to satisfy our hunger. Now we had to climb 1,500 feet of brutal terrain, in thick fog, to reach the crude, unofficial trail back to our tent. |

| It was a landscape of numerous knolls, small lakes, gorges -- with all its usual landmark peaks absolutely obscured. All was soggy, cold and gray. Since we had a map, but no compass, and the sun itself was invisible, we could only head uphill hoping to stay on what we guessed was the right course. By and by (we had no watch!) we were climbing high on a steep slope that seemed to go on and on, forever, since the clouds were ever blocking our view. We could see what seemed like the end, only to soon discover another peak above it. This series of false summit let-downs went on and on, and we grew edgy as the slope grew steeper and ever more loose and jagged. |

| Bleak rough rocks were all around. We felt it probable we were stumbling on or near the summit of Mt. Ferry -- but couldn't be sure. We were very dejected. Looking over one ridge, we got blasted by frigid air that swooped up from a snowfield below. Another slope disappeared into mist, but looked at least safe if not properly in our direction. There was no trail, no vegetation, only sharp rock fragments everywhere. So, what else to do? We swore, bit our lips and began a descent, sliding down loose rocks to who knew where. Then we saw a recognized landmark! |

At last aware exactly how to proceed, our progress was secure -- and spurred by growling hunger. We now could count on reaching our main stash at the tent later in the day, so we ate every bit of the last of our day-pack's meager food, and felt like kings. It no longer mattered that the sun was hidden by clouds, or the trail still dripped wet vegetation to soak us. We knew the way back, and our goal was accomplished.

|

(1992)

Back |

|

|